© 2022 Don Pinson | [Download]

(Link not working? Right-click and select “Save As”.)

Between the years of 1730 and 1770 hundreds of thousands of immigrants poured into the United States. While all the nations of Europe were represented in this sea of people, by far the largest groups were from Scotland and Ireland and came to be called the “Scots-Irish”. Most came into America through Philadelphia and quickly made their way into the American wilderness. These were folks used to life in mountainous terrain, and they rapidly settled into the Allegheny and Appalachian Mountains. With no love of the English crown, since they had been oppressed by the English in their native land, they quickly became Americans and identified with the growing movement toward independence.

Their long history of struggling for freedom made them excellent soldiers in Washington’s continental army. They would figure in key battles throughout the Revolutionary War, often being the group that would turn the tide in battle. For ages they had loved liberty more than life, fighting to the death for the right to local self- government rather than submitting to London’s bureaucrats. They would prove to be the moving force that began the British’ downward spiral toward ultimate defeat.

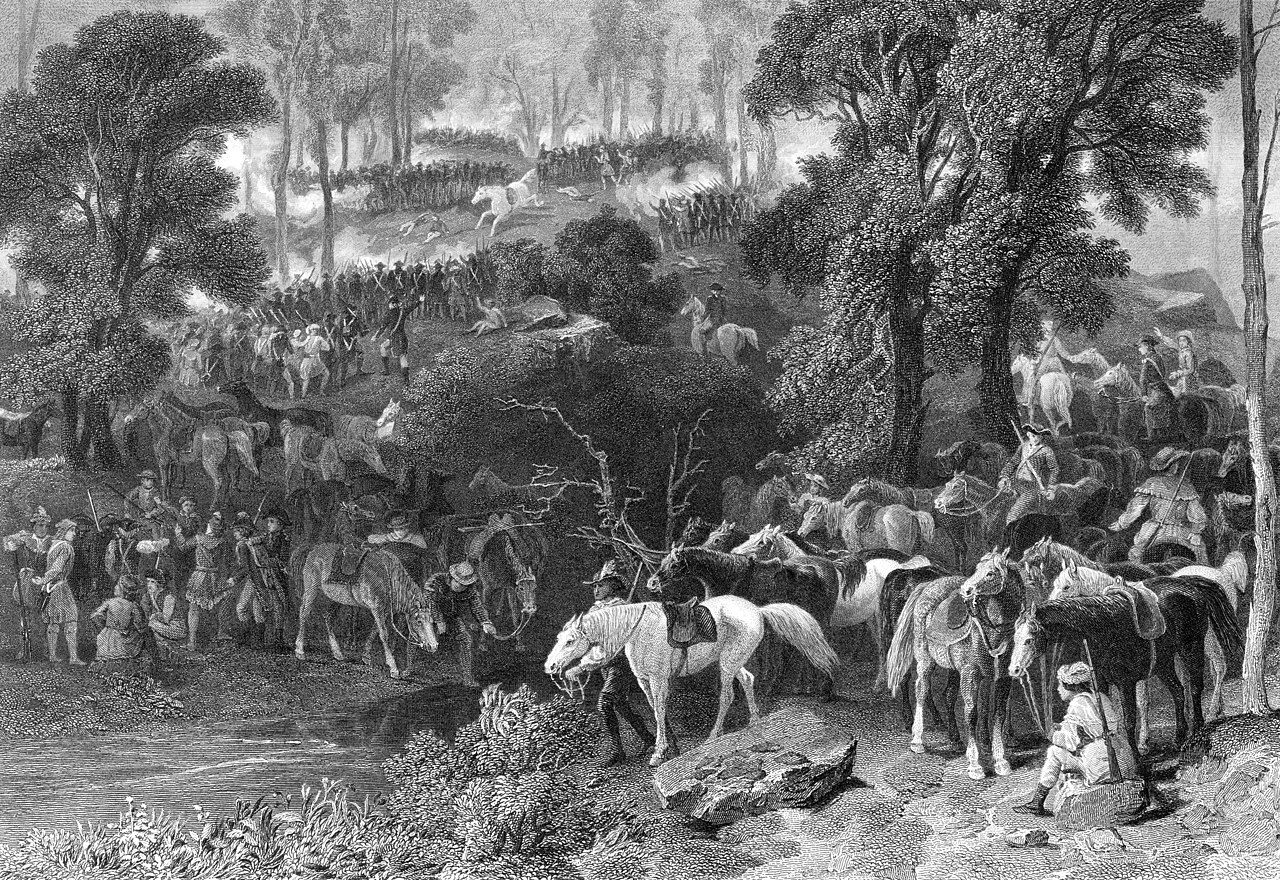

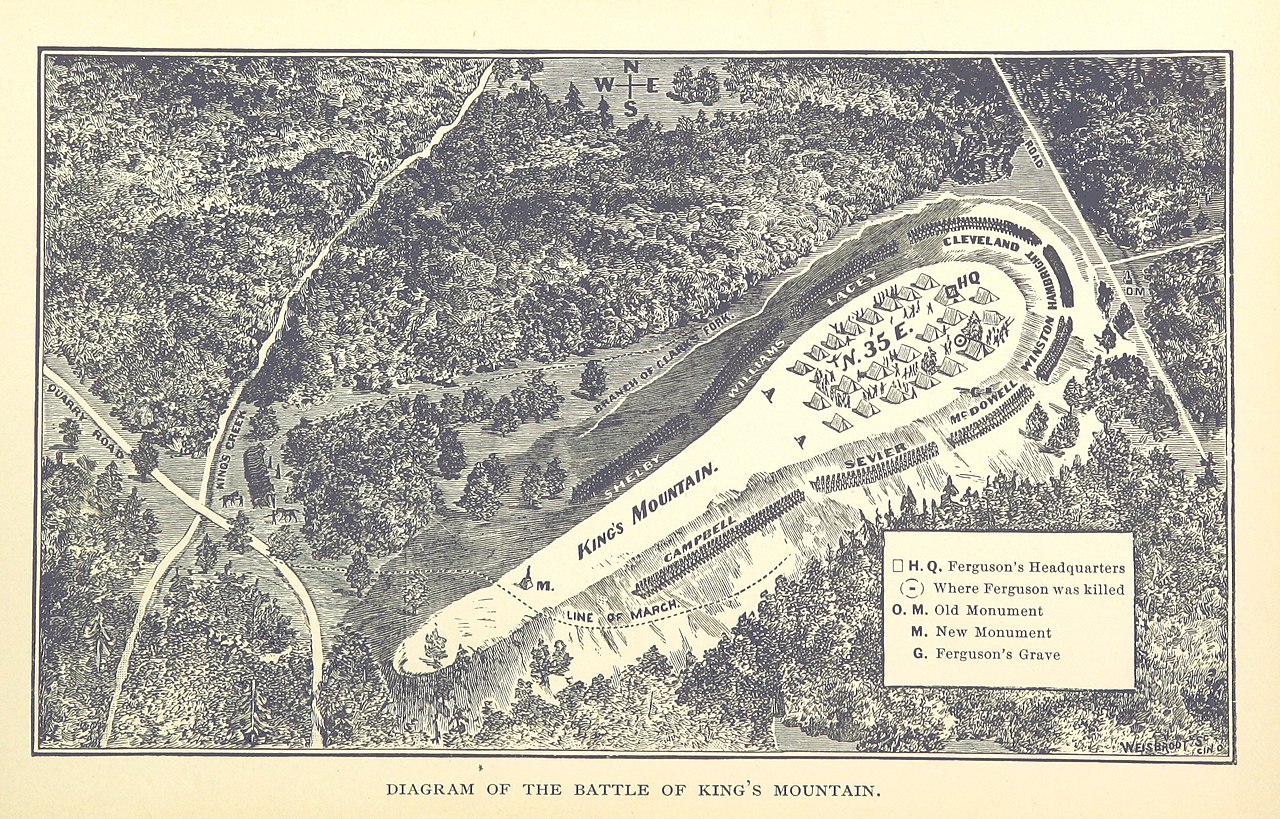

The setting was the border between North and South Carolina. A mountain ridge, 1,700 feet high would be the stage. A very proficient British major under Cornwallis by the name of Ferguson was the British commander. The American command was spread among several local leaders, since the American force was not made up of regular soldiers, but volunteers out of the mountains of the Carolinas, Kentucky, Virginia, and Tennessee. The date was October 7, 1780.

Two commanders among the mountain militia would later be Kentucky and Tennessee’s first governors, Isaac Shelby and John Sevier. Making the mistake of many British army leaders, Ferguson believed the backwoods militiamen to be no match for his 1,200 well-trained and equipped British regulars. Perching atop King’s Mountain he arrogantly boasted to his soldiers that, “…here is a place from which all the rebels outside of hell cannot drive us!” (The American Revolution II, John Fiske (Houghton-Mifflin, 1891), p. 246). But when the mountaineers arrived and hand-picked 1,000 of their force to climb the mountain and attack him, he would find out he was wrong; so wrong it would cost him his life. Climbing slowly and methodically the Kentuckians and Virginians moved up directly toward the front line of the British, while the Carolina and Tennessee volunteers would cover the flanks and cut off any British escape. The aim of the frontiersmen proved deadly while the British were frustrated at having to fire at enemies whose whole bodies they seldom saw. Though falling back at the initial fire into their ranks, Shelby and James Williams’ men hid behind rocks and trees and forced the British to come at them with bayonets. From three sides the volunteers poured volley after volley into the British ranks. The battle didn’t last long as 389 British fell quickly, Ferguson being one of them. The rest of their force surrendered. The mountaineer force had lost only sixty. With 1,100 men gone from Cornwallis’ army, it was the beginning of the end for the British.

The Bible says, “Stand fast in the liberty wherewith Christ has made us free.” (Galatians 5:1)

Will the ‘freedom-loving’ mountain people rise up again to preserve the liberty so hard fought for by their ancestors of these Appalachian hills? Will they be the heroes of the moral battles of our day? Only you hold the answer to that question!

Think about it; because if you don’t, someone else will do your thinking for you—and for your children! And you won’t like what that brings to you. I’m Don Pinson; this has been Think About It.